Introducing: Dr Dianne Mitchell

In October 2017, Dr Dianne Mitchell took up a Junior Research Fellowship at The Queen's College, after completing her PhD at the University of Pennsylvania. Here she tells us a bit about herself and her current projects:

Dianne, you’re currently working on your first book; can you tell us what it’s about?

Absolutely. My book explores how the material realities of sharing lyrics in early modern England shaped the way poets represent intimate contact with their addressees. When Edmund Spenser begins his sonnet collection Amoretti by imagining his beloved’s hands touching the trembling leaves of his poems, he suggests that the act of lyric exchange enables a form of emotional and bodily closeness. But when we look at the poems early moderns actually sent their lovers, friends, patrons, and family members, we find that these texts don’t operate with anything like that kind of familiarity and directness. Over the last four years or so I’ve scoured archives across the US and Britain for artifacts I call “letter-poems”: lyrics that bear signs of postal transmission. Letter-poems tell us that, in practice, contact between poets and their addressees was mediated by scribes and bearers, made communal by sharing with other friends, and distanced by the material conventions of transmission. I argue that these conventions led to formal innovations that afforded new kinds of intimacy. For instance, I’m currently writing about the homosocial practice of recycling loving poems for multiple friends – a practice whose resistance to “singleness” of both emotional commitments and texts led to the ostentatious repetitions of Shakespeare’s Sonnets.

Your career has frequently taken you back and forth between the US and the UK; What are your impressions of the difference between academia in the two countries?

Obviously the biggest difference from my perspective as an early career scholar in the humanities is the nature of the PhD and what a career afterwards looks like. I spent almost six years in graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania, which is actually pretty quick, believe it or not. I had funding and a good stipend the entire time. I dislike the trend here in the UK of only funding some students and not others; I also find it scary that one really seems to need a book contract in order to get a permanent job in the UK. That would be fine if there were infinite postdoctoral fellowships, but sadly that’s not the case (thanks, government cuts!). On the other hand, a great advantage of higher education here in the UK is that wherever you work, you’ll never be too far from colleagues at other institutions. I absolutely love the cross-institution collaboration you see here between humanities departments. By contrast, I have US colleagues who feel very isolated because there are no other universities, or even big cities, within two or three hours’ drive. The question “Is this career really worth it?” comes into play when you are contemplating working somewhere that is potentially a four-hour plane flight from friends, family, and close colleagues. I think our current model of career success glosses over some of these costs.

You’ve previously worked for an entomologist, in a winery, and as a substitute teacher; what’s the most interesting job you’ve ever had outside academia?

I think it’s good to try out a variety of things, if only in order to find out a little bit about what goes on outside the academic bubble! The winery job was a summer gig in my home town in the Finger Lakes region of New York State. It was a fun way to meet people and taste delicious locally produced wines every day. The substitute teaching job involved, let’s say, a different skill set. I actually worked at a state school outside of Oxford. The experience really opened my eyes to the Oxford that exists beyond the University, and to the incredible challenges state school teachers face, often with great skill and sensitivity. I will say this, after walking into a room of thirty-five sixteen-year-olds and teaching them a maths lesson with only about 90 seconds of preparation, no university teaching experience can scare you.

Together with Katherine Hunt you’re organising a conference called “Literary Form After Matter” (22 June 2018, The Queen’s College, Oxford); how did this come about and what are you hoping for from the papers?

Katherine and I are both deeply interested in the relationship between the history of the material text and what’s called the “new formalism”: a return of attention to questions of literary form that is sensitive to historical difference (and often explicitly feminist in nature). The summer before I started my junior research fellowship, we met up at the British Library and began to brainstorm. We knew we wanted short papers that think through the question of whether the “material turn” has actually helped us figure out what we mean by literary form in 2018. It’s been fantastic to collaborate with Katherine, who’s my colleague at The Queen’s College. While planning the conference, we discovered that we had a number of common aims. For instance, it was a priority for us to invite an early career scholar to be one of our keynotes, and we were delighted to get Sophie Butler (UEA) on board. You can submit an abstract to our conference until March 18, 2018: check out the call for papers here!

You also organise a reading group for early career researchers working on the early modern period; what are some of the insights you’ve gained from these sessions?

One insight I’ve gained is that there is a real need among early career researchers to talk about the writing process. For our last meeting, we read a pre-circulated piece reflecting on the experience of turning a dissertation into a book. When you start swapping your own writing practices with ten other people, you realize how much you can learn from colleagues. Yet, there are few fora for sharing and demystifying these kinds of experiences. We’ve been meeting twice a term, and I’d like to make sure that, going forward, at least one session each term offers a chance to talk through particular issues related to the scholarly and public humanities projects we are working on. I’m hoping that our upcoming session, in which we’ll workshop my colleague Edwina Christie’s article on seventeenth-century romance, will open up a conversation about the challenging process of crafting and revising a journal article!

Having already organised a conference and started a reading group, do you have any future projects lined up?

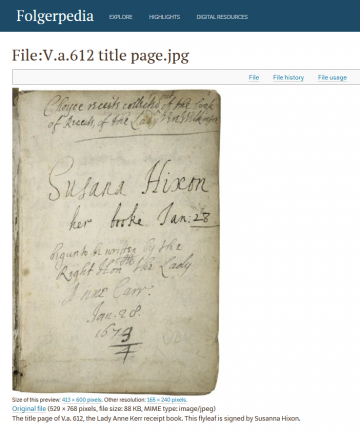

One of the best parts of my JRF is the opportunities it affords to dream up collaborative events. After attending a conference at the Folger Shakespeare library about new directions for teaching and researching with their resource Early Modern Manuscripts Online, I have this crazy idea of organizing a transcribathon in the autumn of 2018. For those who’ve never participated in a transcribathon, it involves getting dozens or even hundreds of people to transcribe digital images of a manuscript (ideally one that’s never been edited before) over a set period of time. I’d love to get Oxford students and staff (and locals!) to transcribe something in the Bodleian collections – perhaps a miscellany of female-authored verse. Transcribathons are a great way to gain intimate knowledge of an early modern text in a group setting, and the crowdsourcing nature of the event means that it’s okay if you can’t read every single word: each page of the manuscript is triple-transcribed and then collated. Also, you can participate for as little or as long as you want. My aim would be to have colleagues around the world dropping in online while a group worked “in person” at a central location in Oxford. The end result would be a transcription of an unpublished text (and new friends). If anyone reading this might be interested in collaborating with me, please drop me an email!

Early Modern Manuscripts Online