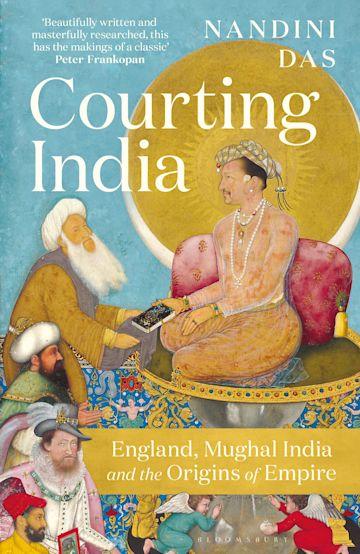

Courting India

On the 9th of March, the Oxford Centre for Early Modern Studies hosted a roundtable discussion on Professor Nandini Das’s recently published book, Courting India: England, Mughal India, and the Origins of Empire. True to the book’s (and CEMS’s) committed interdisciplinarity, Professor Das was joined by Professor Lorna Hutson from the Faculty of English, alongside Professor John-Paul Ghobrial and Dr Yasmin Khan from the History Faculty, and an audience offering questions on literary, historical, artistic, and theological themes.

Professor Das’s book, as she outlined to the audience, concerns the embassy of Sir Thomas Roe, a courtier who had risen from the Elizabethan-Jacobean ‘middling rungs’, and was chosen by James VI and I to lead the first English embassy to the Mughal court of the Emperor Jahangir at Agra from 1615 until 1618. The embassy was an unprecedented joint venture between the crown and the recently founded East India Company, with Roe’s diplomatic and honorific status conferred by James’s authority, but his per diem paid, and his mercantile directives established by the demands of the Company. It was also an abject failure, and a broader subject of Courting India is the disruptions and neuroses that this ‘false start’ has caused for teleological histories and pre-histories of the British Empire. Roe campaigned in vain for trade exclusivity in certain parts of North-Western India, against the hundred-year-old settlement of the Portuguese at Goa in the South, but made little headway, and the company would have to wait until the eighteenth century before the British ‘juggernaut’, with all its expropriation and aggression, was established. Dr Khan memorably called the later activity of the Company Courting India’s ‘noises off’: an indistinct but persistent historical infraction on the less coordinated and bureaucratic activity of Jacobean Anglo-Indian encounter.

William Baffin’s 1619 Map of the Mughal Empire, Known as ‘Thomas Roe’s Map’.

Running through this macro-historical situation of Roe’s embassy was a rich characterisation of Roe himself, whose anxieties and idiosyncrasies occupied much of the panel’s discussion. A wealth of revealing anecdote was offered and commented upon. Roe’s bullish refusal to learn either Persian or Turkish (despite his encouragement of language-learning in his attendants); his fretting over whether to fully prostrate himself when presented to Jahangir; his strikingly personal remark that Jahangir ‘craked like a Northern man’ at jokes: these microscopic indices of Roe’s personality were all reflected upon as indicative of a broader pattern of awkward cultural accommodations made on both sides of the embassy. These patterns, as Professor Das noted, offer a flicker of an alternative history of Anglo-Indian relations to that of eighteenth-century dominion.

A particularly fascinating area of discussion encircled these moments of cultural incommensurability and accommodation. Two encounters stood out as reflective of the complex dynamics of cultural difference and likeness. The first is concerning religion at the Mughal court. The Mughals had quickly realized that it would be impractical to convert the entire sub-continent to Islam, and as such had allowed a certain level of religious diversity at court and in wider society; Jahangir’s father, the Emperor Akbar, also took an intellectual interest in inter-faith discussion. (Though as Professor Das pointed out, the evidence of faith-dependent taxation levels shows that there was by no means religious equality in Mughal India). The resulting presence of Muslims, Hindus, and Jains at Jahangir’s court was something which the English, coming from a country in which Protestantism was at least outwardly imposed at court and in civil life, found particularly puzzling. But the unfamiliarity of this policy cast a long and productive shadow over Roe’s life: in the 1640s, when called to advice Charles I on how to recoup some of the crown’s catastrophically high expenditure, Roe summoned the example of ‘Great Mughal’, and advised Charles to open England for other faiths to conduct their trade. Here, Professor Das called upon her earlier work on travel and memory to show how Roe’s remembered embassy offered the glimpse of an alternative teleology in Anglo-Indian relations, based upon greater efforts of cultural accommodation, and founded on both pragmatic and intellectual grounds.

Abu’l-Hasan’s copy of Dürer’s 'St John The Evangelist', 1600-1.

The second anecdotal example of these complexities of difference and similarity is artistic, reflecting a constant incorporation of Mughal art as a source in Courting India. Art and visuality were central elements of the Mughal court, and Professor Das pointed to the presence at Jahangir’s court of such artists as Abu’l-Hasan, the prodigiously talented miniaturist who at age thirteen drew a remarkable study of Albrecht Dürer’s St. John the Evangelist. The anecdote involves a wager made by Roe with an anonymous Mughal painter, over whether the latter could produce a convincing copy of a miniature by the great English miniaturist Nicholas Hilliard. Roe believed this was impossible, and lost the bet, unable to recognise the original. Art, both literary and visual, was an important medium through which Roe negotiated difference: drawing again on the theme of ‘memorial echoes’, Professor Das suggested that Roe’s strong reaction to the figure of Nur Jahan, Jahangir’s Empress Consort, was influenced by the similarity of her portraits to those of Anna of Denmark, which Roe may have seen. Professor Das also gave a suggestive reading of Ben Jonson’s Epigram to Roe, where the former’s hagiographic image of Roe as a neo-Stoic may have inflected the ambassador’s stubborn, uncompromising, and hopelessly unpragmatic behaviour at Jahangir’s court.

Anonymous Mughal Miniature of a ‘Farangi’ (Foreigner), possibly after Hilliard, c. 1600-1650.

In Professor Hutson’s opening remarks, she singled out as a particularly valuable element of Courting India its resistance to narratives of ‘overturning’, or the all-too-neat ‘reversal’ of a given paradigm. Instead, Courting India attends intimately to the complexity of archives, allowing Roe’s story to develop and subdivide before reflecting on its place in historical time. This attention to minute and mundane detail was also suggested as the central technique by which Professor Das resists Orientalist forms of attention and description, forms which, indeed, can often be traced back to Western comment on the visual opulence of Mughal courts. Considering, alongside court records and diplomatic communiqués, works such as the Ardhakathānaka (The Half-Life Story), the poetic autobiography of a businessman from Agra, the persistence of the everyday in Courting India resists all forms of simplification.

Report by Flynn Allott, DPhil Candidate, Oriel College, Oxford.