Forgery, Imitation, Replication

In Leonardo Sciascia’s novel, The Council of Egypt (1963) a lowly Sicilian cleric, Don Giuseppe Vella, sees his opportunity when he is asked (because he speaks a little Arabic) to play host to a shipwrecked Moroccan ambassador. Asked to show the ambassador a medieval Arabic manuscript in a local monastery, Vella hits on the idea of falsely claiming that the ambassador identified it as a rare and precious codex about the Arab conquest of Sicily. Soon Vella is using all his skills in calligraphy and Arabic ‘translation’ to represent the monastery’s Arabic codex as an authentic Sicilian history. Temporarily famous and lionised, Vella persuades himself that ‘there was more merit in inventing history than in transcribing it from old maps and tablets and ancient tombs’. The eagerness with which even a sceptical Sicilian elite finds reasons to believe the hoax seems to prove him right.

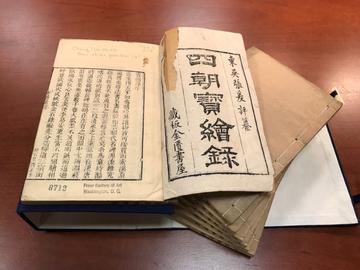

Book Cover: Zhang Taijie, A Record of Treasured Paintings (Baohuilu, 1633).

Oxford CEMS’s second ‘Global Conversation’ of 2023 at Merton on 2 May took up the challenging question of forgery’s relation to the desires of collectors, readers and scholars. A series of excellent talks ranged across the disciplines of art history and literature, from China and the Mughal Empire to the Ottomans, Italy, Portugal and England. JP Park introduced us to his discovery of the astonishing achievement of Zhang Taijie, who in the 17th century forged a comprehensive treasure book of Chinese art, along with the spurious ancient artworks to which it referred. JP showed how Zhang Taijie’s extensive techniques of cross-referencing and allusion were so successful that not only were his 17th forgeries accepted as artworks of much earlier centuries, but his critical commentaries have been transmitted through the centuries into modern art history.

Andrea Mantegna, The Adoration of the Magi (c. 1495-1505).

By contrast, Leah Clark, turning to the circulation of Ottoman, Mamluk and Chinese artworks in fifteenth century Italian courts, asked us to dismantle notions of ‘original’ and ‘copy’, offering instead frames of reference that value mediation, exchange and sensory experience. She explained how stories of ownership attaching to replicas bring a value to the object; how copying itself might be a form of connoisseurship, a way of ‘knowing’ an art object, and how imitating one material under another form (metalwork or porcelain in ceramic) might itself be an index of appreciation and sensory innovation.

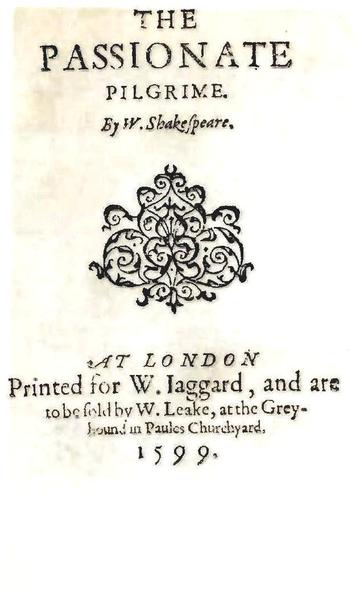

The Passionate Pilgrim (1599).

After a break for tea and (authentic) cake, three more short talks gave us further case studies to puzzle over. Colin Burrow took up the question of the legal centrality of intent – in English law, mens rea – to definitions of forgery. He asked whether we might bracket off the moral language of intentional deception in order to focus on the elements which encouraged readers of The Passionate Pilgrim (1599) — described on its titlepage as ‘by W. Shakespeare’ – to identify particular sonnets with that authorial name. Colin’s paper bore out both JP’s and Leah’s revisionary thinking. On the one hand, the printer William Jaggard, like Zhang Taijie, presciently anticipated the optimum moment in which to exploit the desires of a readership; on the other, his compilation was part of a culture in which, as in fifteenth century Italy, copying an art object had become a form of knowing and discerning.

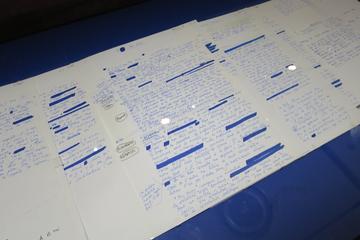

Roland Barthes' drafts of Fragments d’un discours amoureux. Displayed during an exhibition at the BNF in 2015: Les écritures de Roland Barthes, Panorama.

Simon Park then took up this question of ‘the maker’s knowledge’, describing his own perpetration of a hoax when he faked the discovery of a new fragment of Roland Barthes’ Fragments d’un discours amoureux (1977). Simon spoke fascinatingly about how his imitation of Barthes’ critical writing gave him a knowledge that was hard to translate into critical discourse but that also raised questions of the extent to which critical thinking is separable from style. Finally, we were drawn back to Leah’s earlier critique of the transcultural validity of terms like ‘original’ and ‘copy’ in Nandini Das’s eye-opening discussion of Mughal artists at the court of the Emperor Jahangir. Abu’l Hassan’s precocious imitation of Dürer and Bichtir’s portrait of James VI and I were among the many intriguing examples of artistic occidentalism at the Mughal court.

Left: Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings (c. 1615-18). Right: John de Critz the Elder, James I of England (c. 1606).

For all of us, the challenge of ‘Global Conversations’ is the risk we all feel of being ignorant of other disciplines, languages and area studies – that is, of being frauds – but the rewards of juxtaposing these diverse case studies is well worth the risk. Discussion, however tentative, was always thought-provoking. Thanks to everyone who attended and made it possible.

Professor Lorna Hutson 03 May 2023.