Reading for the Food: Masterclass with Leonard Barkan

Leonard Barkan’s recent visit to the UK has occasioned the latest interdisciplinary masterclass organised by Prof Joe Moshenska for the Centre for Early Modern Studies. The topic – food – stemmed from Prof. Barkan’s recent book, The Hungry Eye: Eating, Drinking and European Culture from Rome to the Renaissance (2021). Remarkably, this is not even Barkan’s most recent book: that book, Reading Shakespeare Reading Me (2022), formed the subject of a lecture on the first person in scholarship which Barkan delivered a day before the food masterclass started. Barkan’s lecture offered a fitting starter to the main course and dessert of the two (lunchtime) seminars – attended by graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, and postholders from faculties of art history, English, history, and modern languages – which constituted the CEMS masterclass on food. Indeed, the first person was revealed in both masterclass seminars as key to Barkan’s method of ‘reading for the food’: although representations of food from antiquity to the present have often been interpreted as metaphorical, the metaphor of food, Barkan stressed, ceases at the point of consumption, when food is embodied by the first-person subject, as indeed food must be embodied for us to survive. Accordingly, Barkan emphasised the need to look at food qua food, and to explore how food may have greater meaning in itself than is typically acknowledged.

Adriaen Coorte, Still Life with Asparagus and Red Currants (1696), oil on canvas, 34 x 25 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., no. 2002.122.1.

In the first seminar, Barkan elaborated his anti-symbolic approach to food with an array of visual examples. This included still life paintings of cheese by Clara Peeters, which whetted some whey-craving appetites in the room, and Adriaen Coorte’s Still Life with Asparagus and Red Currants (1696). Some commentators, Barkan said, discuss Coorte’s Still Life with Asparagus as symbolic of human mortality or as an allegory of mutability. Barkan, in contrast, looks at this painting and sees asparagus, skilfully painted with the aim of realistic mimesis. Barkan in this first seminar also discussed several artists’ responses to the Last Supper, digressing into the definition of sop – ‘a piece of bread or the like dipped or steeped in water, wine’ (OED) – in the context of Jesus’ feeding Judas a sop and thus identifying him as a traitor. The method of reading for the food, it was observed, shouldn’t itself be maligned as a sop to the critic. Instead, this method offers a useful means of focusing on materiality, and of yoking supposedly high and low culture – food is often afforded short critical shrift – in our histories of worldly experience.

Joachim Beuckelaer, The Four Elements: Fire (1570), oil on canvas, 157.5 x 215.5 cm, National Gallery, London, NG6588; a kitchen scene with Christ in the house of Martha and Mary in the background.

The second seminar raised further fruitful discussion on the topics of materiality, the worldly, and the somatic. Time in this seminar, for instance, was spent on paintings of Jesus at the house of Martha and Mary by Vermeer, Velázquez, Pieter Aertsen, and Joachim Beuckelaer, with reference to how each artist foregrounds food: discussion here probed the intersections between food, sensuality, and sexuality, and also the importance of work in the production of food for consumption. Contributions from participants then led to reflections on what qualifies as food in the first place: what about breastmilk, or the head of John the Baptist served on a platter? The latter example was taken to illustrate a tendency whereby food shades off into the abject. That tendency is represented more widely by food fragments and rotting scraps of food, all of which may offend the supreme aesthetic criterion of good ‘taste’.

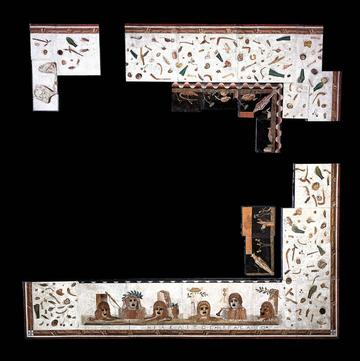

Heraclitus of Rome, Asàrotos òikos (Unswept Floor) (2nd century ce), mosaic, 405 x 405 cm, Museo Gregoriano Profano, Vatican Museums, inv. no. 10132.

Scraps, however, can also become art. This idea was underscored as key, for it mirrors how food, typically abandoned as low-brow at the outskirts of critical inquiry, can and should be brought into sharper focus. The close connections between art and waste, high culture and low culture, and the beautiful and the abject were nowhere more apparent for Barkan than in ‘unswept floor’ mosaics from ancient Greece and Rome, such as the example from Rome in the second-century CE which is partially preserved at the Museo Gregoriano Profano. This particular Unswept Floor lies at the centre of Barkan’s Hungry Eye: it wrote the book for him, Barkan said. The mosaic, itself made from scraps of glass and marble, imitates with striking realism the scraps of food discarded after a banquet. Perhaps the highlight: an inquisitive mouse enjoys the remnants of a walnut shell. All of these scraps would usually have been cleaned up, of course, and yet in this mosaic they take pride of place. Thus the mosaic demonstrates in nuce how food is elevated beyond the merely incidental – though food, as Barkan pointed out, is never ‘mere’. The masterclass never lacked in food for thought.

Heraclitus's 'Unswept Floor' in detail.

John Colley, DPhil candidate, Jesus College, Oxford.