Livery, Skin, and the Early Modern Origins of Whiteness.

On Tuesday 21 February 2023, Oxford's Centre for Early Modern Studies (CEMS) was pleased to host Professor Craig Koslofsky (University of Illinois) for a one-off lecture at Merton College. In this lecture, Professor Koslofsky (Fowler Hamilton Visiting Research Fellow at Christ Church, spring 2023) offered an overview of his research on the global history of skin.

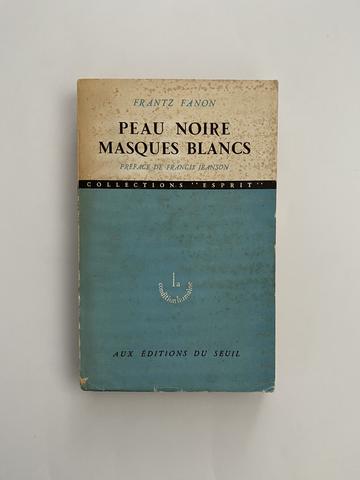

Professor Koslofsky's remarkably wide-ranging presentation began with an introduction to Franz Fanon's Black Skin, White Masks (Peau noire, masques blancs, 1952) and with the following quotation from the introduction to Fanon's 'clinical study':

I seriously hope to persuade my brother, whether black or white, to tear off with all his strength the shameful livery put together by centuries of incomprehension. (Franz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, translated from French by Richard Wilcox (London: Penguin, 2021), p. xii).

Reading Fanon's idea of 'shameful livery' as a metaphor for the process Fanon described as 'epidermalisation' — the forcible, quasi-medicalised reduction of non-white individuals to their skin and/or skin colour — Professor Koslofsky considered how Fanon's concepts might be brought fruitfully to bear upon the highly 'epidermalised' early modern world. With Fanon's Black Skin, White Masks as its starting point, Professor Koslofsky's presentation offered up a broader definition of epidermalisation: understood in this presentation as the fixing of social meaning on the skin through culturally and historically specific practices and discourses.

Having expanded Fanon's concept of epidermalisation, the first part of Professor Koslofsky's presentation contrasted the dishonorable practice of deliberately and permanently marking the skin in early modern Europe (through judicial branding, for example) with the ubiquity of 'positive' dermal marking practices as a form of aesthetic expression elsewhere around the world. Across the Atlantic, Professor Koslofsky demonstrated, early modern Europeans were shocked (and not infrequently appalled) to encounter a highly epidermalised world where bodily modifications and inscriptions were signs of honour and status rather than of penal discredit. A panoply of 'grotesque' bodily modifications — considered by the author to be an assault on the perfect, unmarked body as created by God — can be seen in the frontispiece to John Bulwer's Anthropometamorphosis (editions 1650-58). What was mediately expressed by the sartorial livery of early modern Europeans was found to be strikingly articulated on the very bodies of the epidermalised world beyond. Hence, as Professor Koslofsky revealed, early modern English and French authors came to describe native skin marking or skin colour as 'livery'.

John Bulwer, Anthropometamorphosis (1653), Frontispiece, detail.

Professor Koslofsky then proceeded to discuss the anxieties of colonialist settlers in these epidermalised societies, particularly in the Americas, drawing out intellectual debates about the heritability of skin colour. Were native infants born white, only to be subsequently marked by their environment, diet, and culture, or was their dark skin congenital? More pressingly, what would happen to the white skin of European colonialists if they were to settle in America? Would the descendants of these settlers still resemble the complexion of their forefathers? Incidentally, it was these questions, Professor Koslofsky demonstrated, which prompted vast scientific investigation into the anatomy of skin during the seventeenth century and the gradual decline of medieval humoral ideas about the body.

“Discovery” of the dark rete mucosum and translucent cuticle, from Bernhard Siegfried Albinus, De sede et causa coloris Aethiopum et caeterorum hominum (Leiden, 1737), illustr. Jan Ladmiral.

Having opened up the intellectual and scientific debates intrinsic to the colonisation of the Americas and the wider epidermalised world during the 'Age of Discovery' (1450-1750), Professor Koslofsky's presentation concluded by returning to Fanon and by reflecting on the origins of whiteness. As geo-humoralism receded and differences of 'complexion' came to mean differences of skin colour, Professor Koslofsky concluded, so 'whiteness' came to be understood as a condition of unmarked purity both precarious and powerful, indirectly signified in high-born women's beauty and chastity. One rich example of this, drawn out by Professor Koslofsky's presentation, was the symbolic resonance of blushing. Developing from Angela Rosenthal's research, Professor Koslofsky gave instructive and persuasive examples from Anthony van Dyck's paintings, evincing how the capacity to blush — or rather the obvious legibility of that reddening on otherwise unmarked cheeks — was itself an evanescent sign of whiteness as purity.

Sir Anthony van Dyck, Marchesa Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo, 1623. National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., 1942.9.92.

van Dyck's paintings proved an invaluable jumping off point for a stimulating discussion in the subsequent Q&A session. Professor Koslofsky was more than generous in responding to thoughts from students and faculty members on such diverse topics as the Curse of Ham; albinism and the ambivalent skin of persons of mixed heritage; blushing and dark skin; and diverse responses to the tattooing of Europeans in various early modern European empires.

Sir Anthony van Dyck, Marchesa Elena Grimaldi-Cattaneo, ca. 1622-1623, oil on canvas. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly, 1929.6.155.

Professor Koslofsky also kindly directed those of us interested in further research in the global history of skin to several excitivents taking place in Oxford and beyond later this year. These events are listed below:

1. Christ Church Library, 6-7 March, noon-2pm: exhibit on the history of skin in early modern books.

2. 7-8 July 2023: ”Cultures of Skin: Skin in Literature and Culture, Past, Present, Future,” an international conference at the University of Surrey, UK – see www. culturalskinstudies.com for details.

3. A short documentary on Professor Koslofsky's research about skin in the early modern world is available online here:

www.lisa.gerda-henkel-stiftung.de/videos?language=en

Finally, we also look forward to the forthcoming publication of Professor Koslofsky's next book, co-edited with Katherine Dauge-Roth, Stigma: Marking Skin in the Early Modern World in March.

Professor Craig Koslofsky is Professor of History and Germanic Languages and Literatures at the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign.