Unfinished Conversations: Skill Kissing the Rod 3

Since 2005, when Elizabeth Clarke and Margaret Kean convened ‘Still Kissing the Rod’ at St Hilda’s College, Oxford, foundational research has been done to develop early modern women’s writing as an area of critical inquiry. ‘Unfinished Conversations: Skill Kissing the Rod 3’ — hosted at Merton College, Oxford, on 30 January 2024 — was occasioned by the recent publication of two landmark works: The Oxford Handbook of Early Modern Women's Writing in English, 1540-1700, edited by by Danielle Clarke, Sarah C. E. Ross and Elizabeth Scott-Bauman (2022), and the online Palgrave Encyclopedia of Early Modern Women’s Writing in English, edited by Patricia Pender and Rosalind Smith (2023). These publications provided an august opportunity to take stock of the challenges and opportunities of early modern women’s writing as a field and to examine existing scholarship and pedagogical methods.

The Oxford Handbook of Early Modern Women’s Writing in English, 1540-1700, edited by Danielle Clarke, Sarah C. E. Ross, and Elizabeth Scott-Baumann (2022)

The first part of the day brought together Rosalind Smith and Danielle Clarke in conversation with Ros Ballaster and Virginia Cox. Rosalind initiated the talks with an informative overview of the Palgrave Encyclopedia and the way in which scholars may navigate it as ‘information flâneurs’, to borrow her phrase. Significantly, she spoke of its unique ability to collate large amounts of information, issue entry points into other reference works, and provide various perspectives from which to view its writers and their contexts, both in detail and, importantly, on a larger scale. Danielle’s presentation, which emphasised the porousness of conceptual boundaries in approaches to women’s literature, corresponded tellingly to the digital and hyperlink-friendly format of the Encyclopedia and the ways in which this online database and the Oxford Handbook productively complement each other. Danielle’s talk revolved around questions of visibility: how might we negotiate archival bias and identify those who continue to be excluded from historical records? How might attention to categories of gender inadvertently obscure the ways in which they are themselves constitutive of other, intersecting identities, including those related to status, race, religion, and transnationality, to name a few?

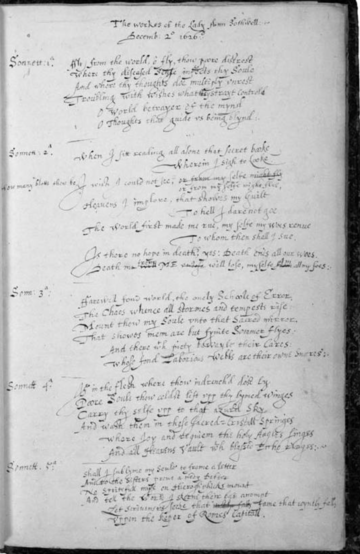

Folger Shakespeare Library (Folger MS V.b.198)

An important question posed by Ros Ballaster framed subsequent discussion: how do we challenge what we think we know? In her response to Rosalind and Danielle’s presentations, Ros commented on the pressing need for satisfactory primary editions to enable the classroom dissemination of women’s writing, and to prevent the tendency of critical work in the early modern period to fall into disaggregated pools of interest, from which little cross-fertilisation can easily occur. These thoughts were echoed by Virginia, who spoke bracingly of the very different context of sixteenth–century Italy, in which women writers, such as Vittoria Colonna, were relatively integrated into elite literary culture. Virginia stressed the value of attending to women writers in non-English contexts. Comparison, Virginia stated, is vital to the work of analysing the specific conditions under which women write and the genres in which they choose to write, in different cultures.

Vittoria Colonna, by Sebastiano del Piombo (c. 1520)

The second session included two more illuminating presentations by Elizabeth Scott-Baumann and Sarah Ross, who put into practice many of the theoretical questions and concerns that had been raised in the earlier part of the afternoon. Elizabeth highlighted the need to consider women writers in this period not simply as participants in a male-dominated canon, but rather as agents of real historical change. Her presentation drew attention to the ways in which we must acknowledge early modern women writers for those characteristics that, in many cases, they were contemporaneously already recognised for: their originality, singularity, and matchlessness. Crucially, Elizabeth argued that these apparently laudatory adjectives become, for these women, impasses, or rhetorical mechanisms that serve to disrupt their ability to become literary models for imitation. Sarah's presentation picked up on these ideas of canonicity — how literary reputation is acquired and how it must be sustained — and, drawing her insights from her teaching of women's writings in New Zealand, observed the ways in which place, and a country's willingness to rethink its own history, can correspondingly allow fixed notions of canonicity to yield. Notably, Sarah made the point that many of the methodologies and techniques that have been curated through attention to women's writings provide an important paradigm to re-consider the canon from all angles, and not merely from a gendered standpoint. As she put it, ‘diverse voices matter aesthetically, as well as politically’.

‘Unfinished Conversations’ was rounded off with closing remarks by Diane Purkiss, who called upon researchers in the early modern period to adopt the approaches that have been espoused by scholars who work with women's writings, and to take into account the voices of early modern women: not only as a matter of ethical importance but also of historical accuracy. Diane reminded us to probe our own notions of gender, to continue to view its categories as necessarily indeterminate and unstable, and to call into question accepted conclusions and modes of thinking. It was a pleasure to witness such thoughtful and insightful discussion, and particularly to hear our speakers reflecting on their own previous work and the extent to which the field has developed so significantly in recent years. The lively Q&A session which wrapped up the event showed how stimulating it had been to listen to these still unfinished conversations.

Report by Camille Gontarek.